Escaping the data science death spiral

How today's Machine Learning technology forces us into wasteful processes and how we can escape them

2021-02-09 by Baxter Eaves in [data science, ai]

After three years in development, the recommendations of a multi-million-dollar decision support project are delivered to a committee of decision-makers who patently ignore them. A nine-figure data-science company lays off 60% of its workforce after two years failing to develop a Machine Learning (ML) solution that can bring value to its target market. A hospital scrubs its efforts to integrate clinical support software after failing to make useful recommendations, more than three years and $60 million later. Mega-scale data science waste is commonplace.

The data science process is hard. It is inefficient, error-prone, and fragile. It is full of iteration and cycles: we do not like what we are producing, so we take a few steps back, tweak, and try again. Every step requires communication with subject area experts and stakeholders; it requires those subject area experts to stop their work to ensure that our work is valid. It requires careful archival and documentation of all previous action to ensure reproducibility, so we can continually progress toward the goal and avoid tripping over our past failures. Cycles are fragile. Every cycle presents an opportunity for the process to fail. This fragility incurs a great deal of waste — from the work required to support ML infrastructure, to the domain-specific ML solutions.

The standard data science process: CRISP-DM

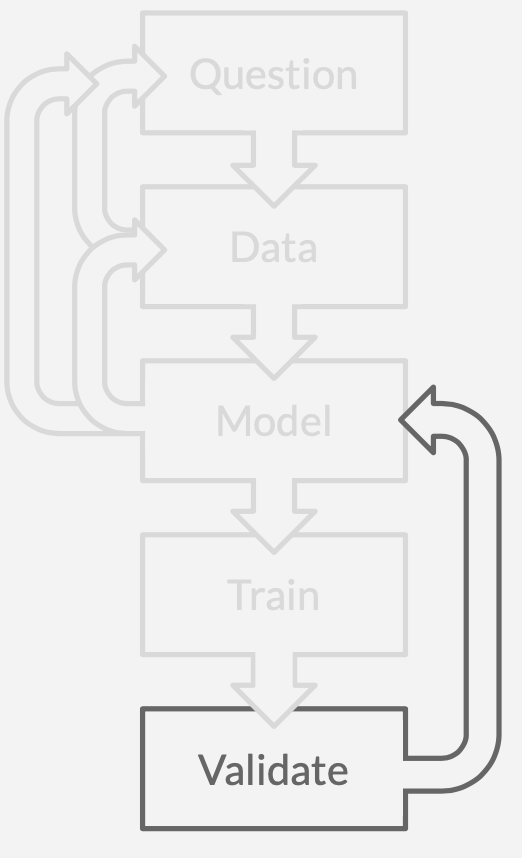

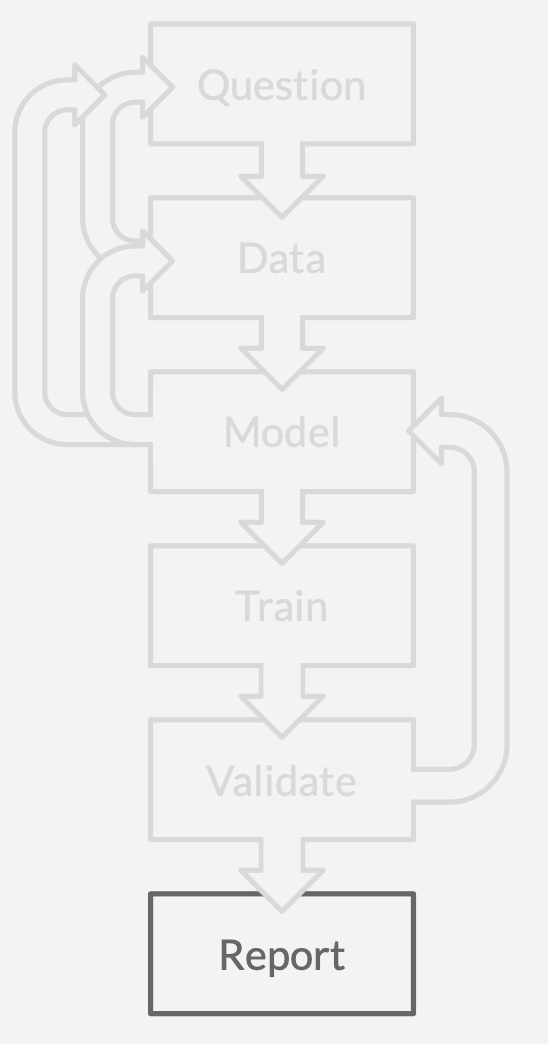

If you are a data scientist, you probably use an analytics process called Cross-industry standard process for data mining or CRISP-DM. You might not be aware what you do is called "CRISP-DM", but this is how everybody does analytics because it is the only workflow that makes sense with today's Machine Learning technology. It goes like this:

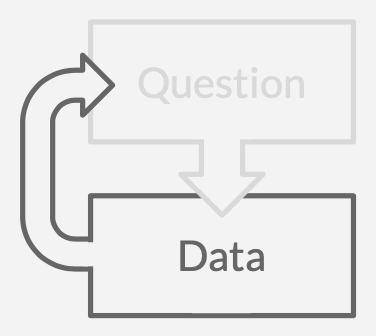

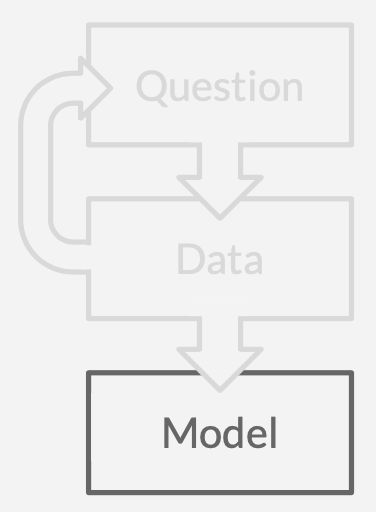

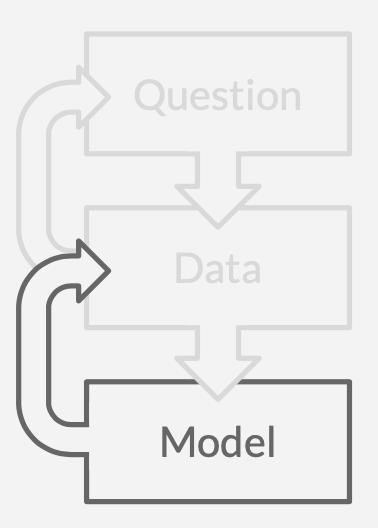

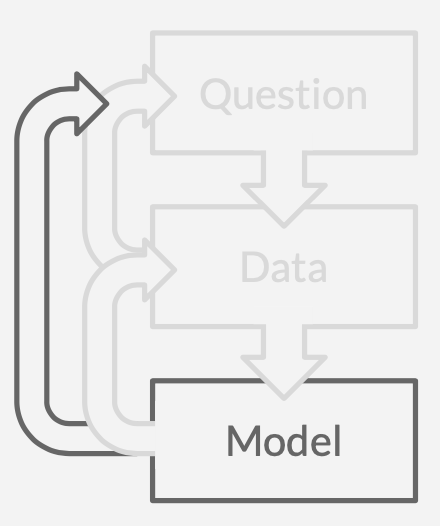

You start by identifying a question that would be valuable to answer.

Then you must find data that support answering your question.

However, it turns out you do not have — or cannot get — the data you need, so you must reformulate the question to reflect the state of the data.

Then you choose from one of infinite Machine Learning models, each with a legion of parameters, hyperparameters, and optional add-ons.

Nevertheless, the model you chose does not support your data, so you have to transform the input. You may need to:

- Encode your categorical values as continuous (e.g., one-hot)

- Transform data that lie across unfavorable support

- Transform data that do not adhere to the model's assumptions, such as normality

- Fill in missing data or throw out entire records with missing values

Maybe you cannot find a model that answers the exact question you want to ask with the data you have.You'll have to ask an adjacent question.

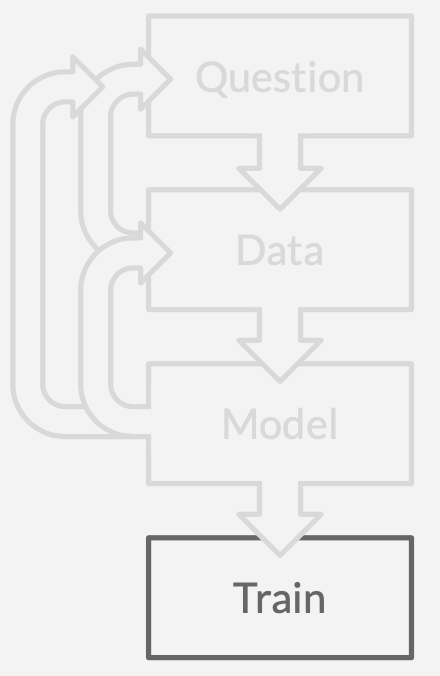

Once you get the question, your data, and the first-try model sorted out, you can train the model.

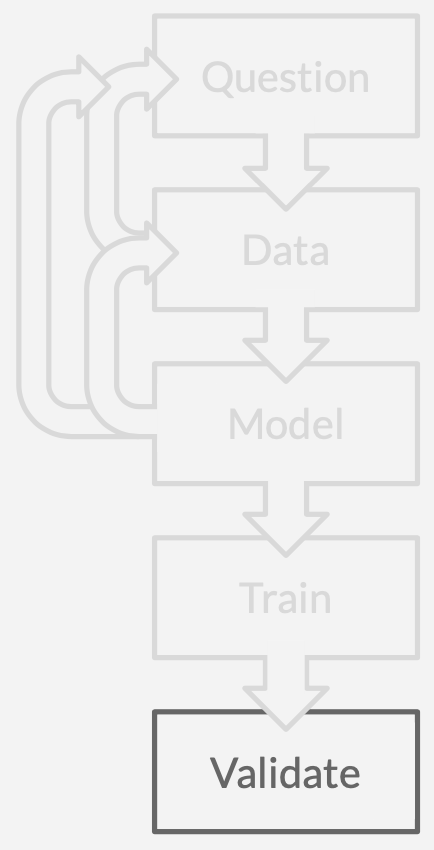

Now, you validate/score the model.

The model does not perform. Things rarely work on the first try.So you tweak the model or select a different model entirely.

Then one of two things happens: after several iterations you hit a performance optimum, after which further effort is unrewarded; or you hit your deadline. In either case, it is time to report.Congrats! 🥳 You have answered a question!

Your stakeholders have new questions. Time to do it again.

Things to note:

- There are nearly as many paths backward as there are paths forward.

- It takes a significant amount of iterative work to answer a single question.

- People are doing most of this work; not AI.

- Sometimes you cannot answer the question because the information does not exist in the data.

- The question you end up answering is often not the one you set out to answer.

The process eventually begins to resemble a game of Chutes and Ladders. If you are lucky, you will always progress — up the ladders — toward an answer. However, we inevitably step into one of the many modeling pitfalls — falling down chutes — having to iterate and try again. Unfortunately pitfalls are built into the process, so we can expect to fall a lot.

The Death Spiral

The whole data science cycle is rough, but the model - train - validate process is a Death Spiral. This cycle is where I have seen the most data science projects go off the rails. Many elements collide to make this part of the process particularly treacherous, but most of the trouble is in measuring and maximizing performance.

You can't prove a negative

Machine learning does not give you a good way to know whether your question is answerable with your data or how well you should expect to do. The first time you try a model, you are likely to fail. Your options are then to find a model that will work, or to prove that no model will work. You must succeed, or you must prove unicorns do not exist. Under some circumstances, if you have the math and the problem is well-behaved, you may be able to mathematically prove that modeling is impossible. But, alas, in my experience, mathematical proof is not compelling to stakeholders. People want and understand empirical results. In practice, the only way to prove that no model will work — or no model will work better — is by deduction: to try everything.

Thanks to the speed of research (there were 163 AI papers published to arXiv in the first 4 days of February) and combinatorial expansion, there are innumerable things to try. And since none of these things quite fit your question and your data, there is always something to blame. "Well, this model does not work well with categorical data, so maybe we could try a different encoding or embedding", "This deep network only has two layers, so it's probably not very expressive", or "We have a lot of missing data, and we've only tried this one imputation method".

Communicating can cost as much as not communicating

In complex domains, like health, biotech, and engineering, where there is extensive science involved and high cost for failure, domain experts must be involved in every step of the process (apart from training). Each step requires e-mailing an expert, scheduling time — days or weeks out — for them to stop what they are doing, and then sitting with them so they can tell us what is wrong and what is right. But communication is a bottleneck. There are two options

- We communicate properly, as frequently as CRISP-DM requires, and risk both annoying our experts and dragging out our project out by months (or longer).

- We do not communicate and risk delivering something likely to fail or to be rejected by decision-makers.

Stakeholder rejection may rightly occur because, in failing to consult decision-makers, we have not understood their needs and have delivered something unwanted or unusable; or because we have made something opaque (Machine Learning is opaque by nature), which they do not understand and cannot be expected to trust.

As a result of all of this, it is common for data science projects to be shelved after months or even years of investment and development.

Why does the data science Death Spiral exist?

The Data Science Death Spiral exists because Machine Learning is, and always has been, focused on modeling questions. What is the value of Y given X? Which data are similar? What factors determine Z? Machine learning assumes the user has a well-defined problem with nice, neat, and complete data. This is rarely the case.

Because Machine Learning focuses on modeling individual questions, the standard data science process must focus on modeling questions; so the standard process is good when you have a well-defined problem and nice data. It is bad when you have a nebulous problem and ugly data, and is disastrous when exploring. And if it is disastrous for exploration, it disastrous for innovation.

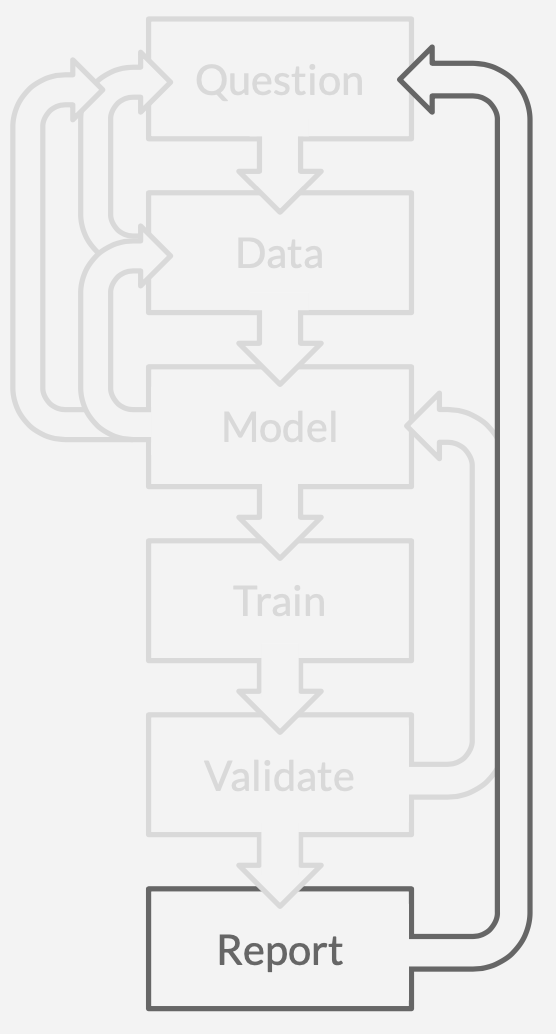

A better data science process through humanistic systems

People do not model questions. You do not have to know what you want to learn before you learn it. You go out into the world, you observe data, and learn from those data. You learn about the process that produced the data: the world.

What if we had Machine Learning or artificial intelligence technology focused on modeling the whole data rather than just modeling single questions? We would be able to answer any number of questions within the realm of our data without re-modeling, re-training or re-validating. We would know which questions we'd be able to answer and how well.

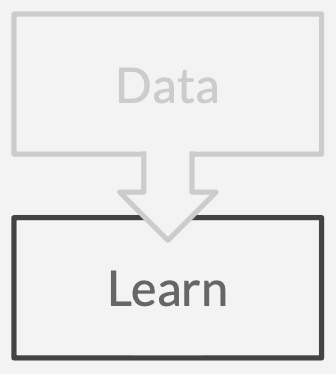

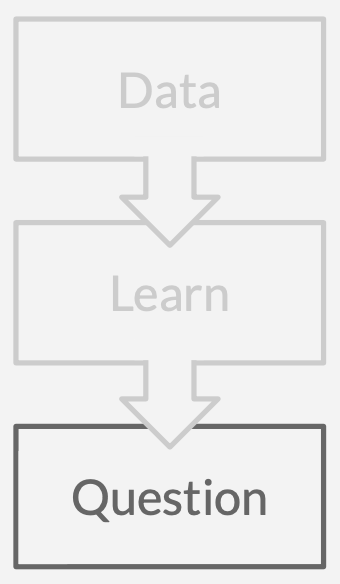

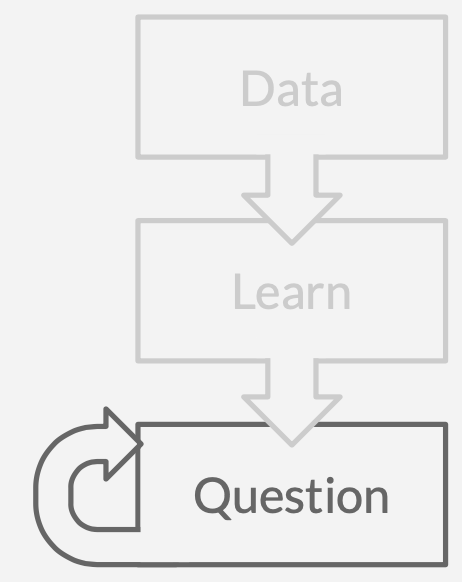

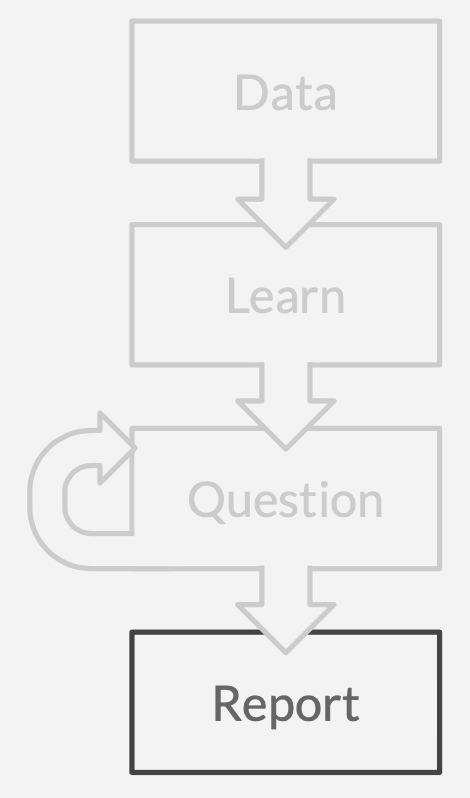

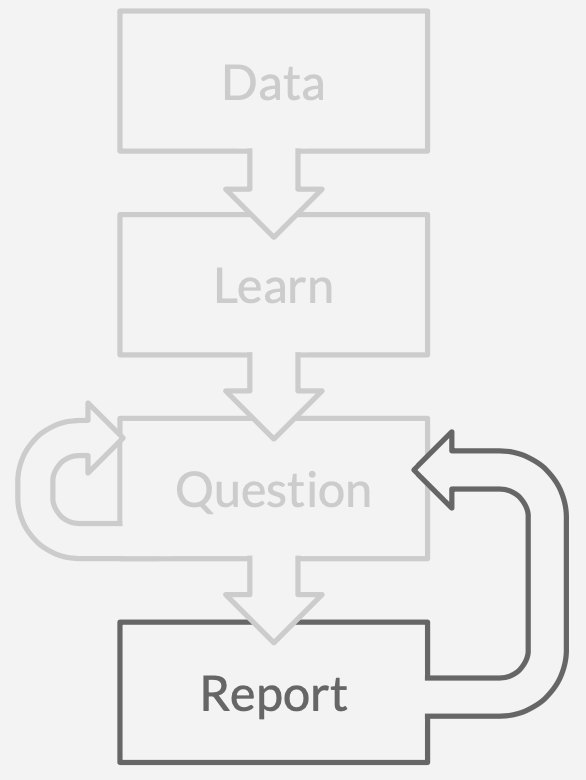

The data science process would look like this:

Get a vaguely coherent dataset.

Learn a causal model that explains the data.

Ask a question.

Ask more questions.

Report to stakeholders.

Ask their questions.

The first thing to notice is that there are far fewer steps and that every step takes us closer to where we want to be. The key in this process is asking sensible questions. Asking sensible questions requires deep domain expertise, so it would be most effective for this Data Science process to be run by a domain expert.

Eliminating iteration through up-front learning and turning a question-modeling system into a question-answering system significantly streamlines discovery and reduces time to production. Under this process, discovery-to-production takes hours or days rather than months or years.

And the best part is: this technology exists today. You can check out what this looks like in practice here.

When we consult for clients, we take their data, feed it through Reformer, and wait until the client has an hour or so to sit with us. Then we let them do our job for us. We sit and translate their questions into Reformer language (which they could do independently with a bit of training) and get feedback in real-time.

It sounds like a racket, but none of us Redpollers has decades of experience in orthopedics, aircraft maintenance, or plant breeding to call upon. We do not know which questions to ask or which insights are potentially novel. It would be arrogant to think that any of us laypeople could solve these problems by blindly throwing AI at a dataset.

Limitations of the humanistic approach

We built Reformer on humanistic AI. Humanistic AI allows us to chew through analyses. It is especially powerful for discovery and green-fielding: getting answers from your data when there is no preexisting model or no satisfactory preexisting model. If you are considering dropping a dataset into a random forest or neural net to see what comes out, your experience would be much improved using a humanistic AI system. That said, there are situations when you might want to go another route.

The humanistic approach is fast because it is flexible, and it is flexible because it makes few assumptions. This is how it can go from nothing to a causal model. A model that makes strong assumptions (that are also correct) will better account for the data. However, developing that domain-specific model takes a lot of science and iteration. The humanistic approach can get you 90% of the way there by allowing you to check your modeling assumptions before you start modeling.

Wrapping up

Data science is a difficult process. Creating production models takes significant human and machine resources. Data science is also a wasteful process because one can never know 1) whether what one wants to do is possible or 2) whether the result will be accepted/trusted by the stakeholder.

The primary contributor to data science's difficulty and wastefulness is that Machine Learning structures lend themselves to inefficient modeling approaches. Machine learning only models specific questions, which places unreasonable demands on the practitioner. These demands are that the data are well-behaved and complete, and the underlying question is well-formed. Alternatively, humanistic systems model data, which allows the user flexibility in both the state of the data and the statement — or existence — of the question. The result is the elimination of the vast majority of backtracking and iteration, and the transformation of a months-long process into a weekend project.

Key points

- The standard data science process, CRISP-DM, is slow and wasteful. It has as many paths away from answers as toward them; and has cycles where the process breaks down.

- CRISP-DM's design was meant to compensate for today's inadequate Machine Learning models.

- Today's Machine Learning is question-oriented rather than data-oriented; therefore one Machine Learning model can address only one question.

- Data-oriented, humanistic AI enables a much simpler workflow in which all paths point toward answers, and the only cycle is answering more questions.

- The humanistic workflow enables immediate ask-and-answer capabilities, enabling stakeholders to directly engage in the discovery process.