Why we are using plant breeding to test defense AI

Like the battlefield, nature is a complex and unpredictable system that crushes best-laid plans under constant and unprecedented change

2020-04-23 by Baxter Eaves in [news, ai]

The term "Defense A.I." elicits certain imagery. Something like NORAD. A room filled with computer terminals and wall displays of satellite imagery, and Matthew Broderick teaching a machine the futility of tic-tac-toe. When I think of plant breeding I remember a trip to a corn breeding facility I took years back. To prevent unintended pollination, the fields were full of high-schoolers in PPE putting paper bags over the corn plants. Certainly the cornfield could not be more different than the battlefield. So why is it that we are using plant breeding as a testbed to develop the AI we are building for DARPA?

In this post, I will discuss DARPA's SAIL-ON program, under which we are developing the OTACON platform, and discuss how plant breeding wrestles with all (and more) of the problems SAIL-ON hopes to address.

Novelty and DARPA's SAIL-ON Program

Along with our colleagues at Rutgers University, we are developing AI for DARPA under the SAIL-ON program. The objective of the SAIL-ON program is to make learning machines that are more robust to different types of novelty in the world. According to DARPA (source):

For AI systems to effectively partner with humans across a spectrum of military applications, intelligent machines need to graduate from closed-world problem solving within confined boundaries to open-world challenges characterized by fluid and novel situations.

Novelty takes many forms.

There are single odd examples. Say an image classifier trained to classify images of fruits receives an image of a toad. How will the machine react? A machine that knows only fruits, may pick up on the green bumpy skin and may, with high certainty, classify the toad as an avocado. Rather we would like the machine to recognize the toad's weirdness and react to it. Perhaps by discarding the example, creating a new class of item around that example, or by asking a human for help. Recognizing novel examples is especially important for preventing attacks. An attacker may make changes to an image that are imperceptible to a human, but that changes the classifier results dramatically (such attacks can do things like cause a machine to read a stop sign as speed limit 45 sign).

Novelty also arises from changes in the way the world is represented or in the dynamics of the world itself. When a person learns to play go, they typically learn on a small 9-by-9 board then eventually graduate to a standard 19-by-19 board. This helps new players to learn fundamentals by keeping the focus on a small area. In contrast, a machine would have to learn 9-by-9 and 19-by-19 go as separate games; it could not transfer its knowledge from one board size to another. And then what if you decide to keep score differently in the middle of the game, or a third player joins in? Again, these are novel situations that a human can handle with ease, but that a machine must be retrained or redesigned to do.

Sources of novelty

One of the things we need to do before we determine how well we can detect and react to novelty is to define what novelty is and where it comes from. SAIL-ON's novelty hierarchy, as laid out in the announcement, is the first attempt at this. I should note that other folks have different thoughts about what novelty is and is not, and how it should be structured theoretically, and are working toward a more formal computational theory of novelty. For the purposes of this post, we will use the following simple hierarchy:

- Class: Previously unseen class or category of object (e.g. new dog breed or type of vehicle)

- Features: Change in how data features are specified or the addition/removal of features (e.g. change of coordinate system).

- Internal Dynamics: Internal change in the system governing how the data are generated (e.g. gravity becomes stronger).

- External Dynamics: Changes in features that are not accounted for by the data that affect the collected features (e.g. unmeasured environmental variables)

- Agent dynamics: Changes in objectives or in the effect of an agent's actions

Plant breeding

Modern plant breeding constantly contends with all of these levels of novelty.

To greatly simplify, plant breeding works like this: we have a portfolio of plants from which we choose pairs to breed in order to achieve some objective — usually to improve performance. In corn, we might wish to maximize grain yield.

From our portfolio, we choose a set of breeding pairs. For each pair, we grow both plants and breed them. From this breeding we achieve a set of crosses, which we plant, grow, and measure. We advance the things we like and forget about the things we do not. New crosses are usually subject to years of further testing and modification. Additional modification is done via other breeding techniques like back-crossing and selfing, and by biotech modification like gene engineering. Plants that make it through the gauntlet become products and find themselves as a part of the starting portfolio for future breeding.

Molecular Breeding

Molecular breeding is breeding using molecular tools — genetics — to inform breeding decisions. This is a common technique in plant and animal breeding. Genetics data are used for a couple of purposes: to get an idea of the performance of a cross without having to grow it, and to ensure genetic diversity. If we have enough data relating the genetics of plants to their phenotypes (observable traits like grain yield and disease resistance) we can predict the phenotype from genotype. But selecting only the highest-performing individuals will likely reduce our genetic diversity. This is bad because if a new disease comes along that our plants are not resistant to they could be wiped out. We could lose everything. We need diverse genetic material for resistance.

Of course, neither prediction nor diversity are as simple as that. Genetics are extremely complex and you would need an unattainable amount of data to account for that complexity. The prediction is made more complicated by the environment, which influences the development of organisms through epigenetic and external factors.

Genetic diversity is a fairly well-defined concept, but it is not the only type of diversity. In the age of machine learning, breeders must also breed for epistemic diversity — diversity of knowledge created. That is, breeders must select crosses that sustain and improve learning.

The Novelty in the Breeding Process

Breeding is a game of novelty. Sometimes you seek it out and sometimes you fight with it. The success of a molecular breeding program is determined by its ability to identify and characterize novelty.

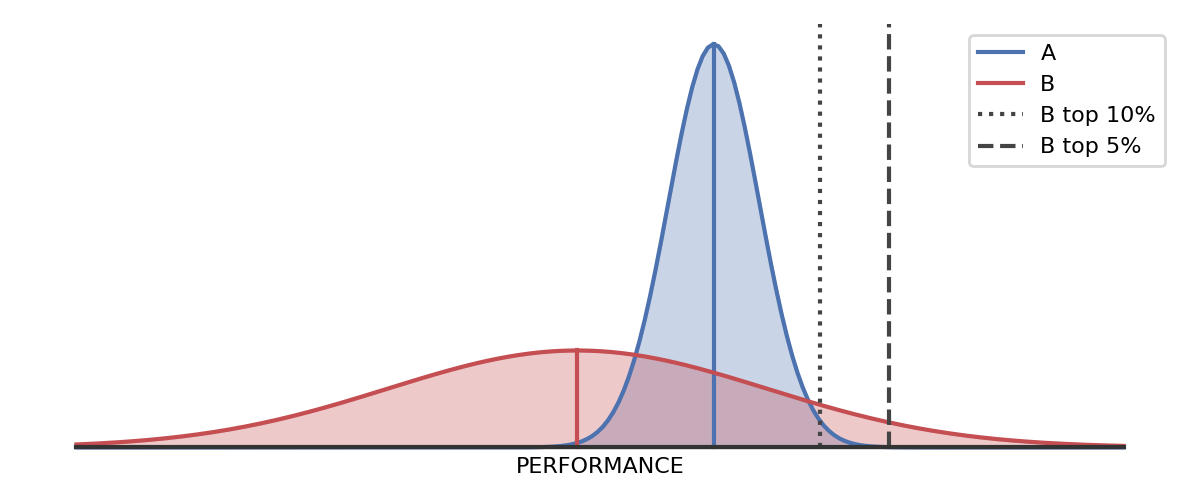

The performance criterion itself is based on novelty. A breeder is not looking for the cross with the highest predicted performance, but the highest probability of producing a high performer. We are looking for game-changing genetics, not incremental changes. We are looking for the cross that will produce the most novel, highest performing plant. Imagine that the performance of a plant follows a bell curve (see Figure 1). Let us say that plant A has a high probability of performing well with little variance and that plant B is likely to perform poorer than A. Which do we choose? You may think A, but the answer is not so straight forward. What if B has a high variance? B might perform worse the A on average, but if the performance distribution of B is wider than A, B's best performers could vastly outperform A's best performers. Let us say that B has a 5% chance of producing a plant better than 99% of A's. As breeders, since we are talking about plants we can take the scattergun approach; we can plant 100, and expect around five really awesome plants — five really awesome sets of genetics. This is why we seek out novelty, but the world of biology is filled with potentially confounding novelty that we must detect and react to in order to achieve our goals.

Figure 1. B (red) performs worse than A (blue) 75% of the time, but 5% of plants from B will outperform 99% of plants from A.

Evolution is fueled by novelty. When we make a cross we receive new genetics created by recombination and mutation. When we develop the individual, the development of that individual is subject to environmental and epigenetic effects, which the sequence data do not account for.

To relate back to our simplified novelty hierarchy:

- Class: A new gene would represent a new feature class. A new phenotype or set of phenotypes would represent a novel class, e.g. a Red Labrador Retriever.

- Features: Additional measurements or features. Often in breeding different measurements are taken depending on the performance of the individual. Some measurements are expensive or time-consuming, and are not conducted on individuals that will be removed from the pipeline. Additionally, as sequencing technology changes, different genetic marker sets of different resolutions will be collected.

- Internal Dynamics: Movement of genes in the feature space. Several genetic mechanisms cause parts of DNA that influence certain phenotypes to move positions. This results in changes in the causal structure in parts of that data, which is something that is very difficult for today's AI to deal with.

- External Dynamics: Environmental factors affect physical development through several mechanisms that present themselves differently depending on other environmental factors. A epigenetic effect might be easier to tease apart from plants grown in a growth chamber than plants grown in the field.

- Agent dynamics: Breeding objectives change, for example in the face of a new disease or pest, or when trying to develop a new class of product, such as short-stature corn.

In plant breeding, we are also generating our own training data, so the decisions we make not only influence our ability to deliver a great product and maintain diversity, but also influence our ability to make informed decisions and innovate in the future.

Wrap up

The reason that we chose plant breeding as a platform to test the general-purpose AI we are building for DARPA is clear: plant breeding a game of characterizing and exploiting — of mastering — novelty. We believe that nature provides the best examples of the open-world challenges characterized by fluid and novel situations that SAIL-ON seeks to address.

Key Points

- DARPA's SAIL-ON program focuses on detecting and reacting to different types of novelty

- Plant breeding supported by genetics data is subject to all these types of novelty and then some

- The goals of plant breeding can be defined in terms of balancing seeking and exploiting desirable forms of novelty