Explainable AI is not enough.

Explaining black box AI won't prevent problems; it will make them worse.

2019-10-01 by Baxter Eaves in [ai, ethics]

Modern AI are black boxes. They hide what they know. This is a problem if we want to use AI to assist decision makers in high-risk tasks like medical treatment (clinical decision support) or military operations where lives are at stake. For AI to be safely usable in tasks like these it must be completely transparent, auditable, and explainable. In this post, I'll discuss what explainable AI (XAI) is, what it should mean to explain AI, and how the current focus on explanation not only fails to make AI safe, but makes it more dangerous.

Problem: AI are black boxes

AI are epistemically opaque. They hide their knowledge away. And even if you use a method to look in the black box, the knowledge inside doesn't makes sense; it doesn't map on to anything in the world. This makes it impossible to use AI (safely and responsibly) in many domains. For example, in defense, when someone makes a decision, they sign their name to a sheet of letterhead and they become legally responsible for the outcomes of that decision. Thousands of lives and the fate of nations potentially hang in the balance, so obviously they're not going to just blindly trust the word of what is effectively a magic 8-ball. They need to know where the machine's decision comes from, what the machine knows, when it fails, when it succeeds; when it can be trusted. To this end DARPA launched the Explainable AI (XAI) program, which aims to fund development of AI technologies that answer these questions.

Solution: Explainable AI

According to (former) XAI program manager David Gunning (PDF source):

The current generation of AI systems offer tremendous benefits, but their effectiveness will be limited by the machine's inability to explain its decisions and actions to users.

If we're using AI in finance, security, medicine, or the military, there are a few key questions an AI needs to answer. According to the program summary:

- Why did you do that?

- Why not something else?

- When do you succeed?

- When do you fail?

- When can I trust you?

- How to I correct and error?

In a nut shell, explainable AI is meant to be AI that is able to be made completely transparent and intuitive to its decision maker. This has less to do with explanation and more to do with interpretability and understanding. All of the above questions can be answered by a human user who is able to completely understand the structure of the machine knowledge.

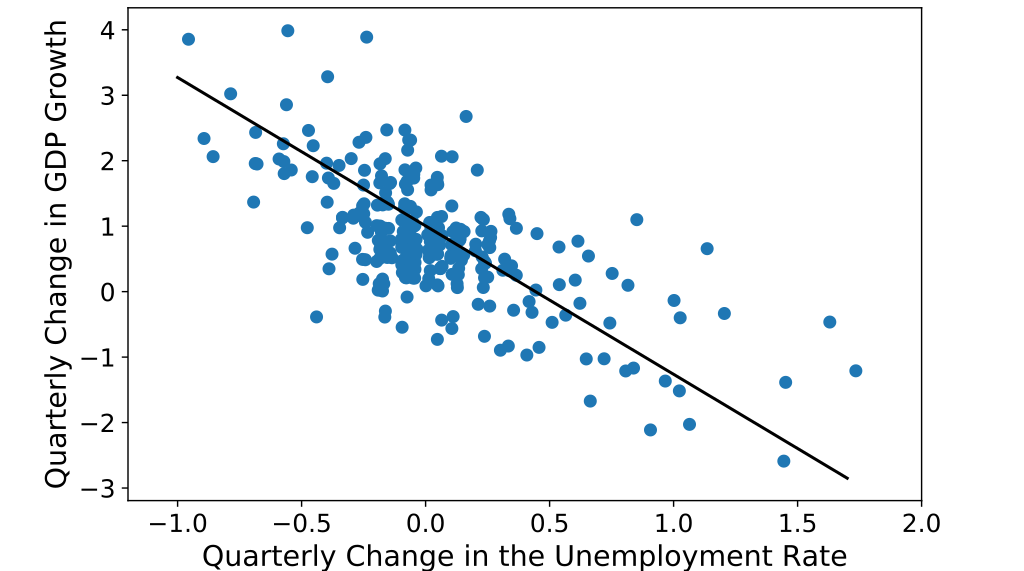

For example, a linear regression is easy to understand. It's just a line. In the figure below it is easy to see that the model has learned that change in GDP growth decreases as the change in unemployment rate increases, and that the variance, or error, is pretty constant through the observable region. Of course, linear regression is not a particularly generalizable or powerful when it comes to learning from arbitrarily complex data.

Above: Figure 1. Linear regression predicting GDP growth as a function of unemployment. It is easy to see that the model has learned that the change in GDP growth decreases as the change in unemployment rate increases (Source from Wikipedia user Acheck10).

Making interpretable models that are generalizable, powerful, and fast is incredibly hard, so the bulk of explainable AI research (both separate and as a part of the XAI program) focuses on explaining the predictions and decisions of the types of AI we already have. To relate to the XAI program objectives, it means that researchers are focusing only on the "Why did you do that?" and "Why not something else?" questions. Unfortunately focusing on the explanation part of explainable AI won't solve AI's safety problems. It will likely make them worse.

Problems with explanation for black box AI

Some problems with explanation of AI come from the after-the-fact nature of explanation; others come from the mechanics of human-human interaction, which arise from humans' tendency to project humanity onto -- or anthropomorphize -- machines.

Explanations are excuses

The most glaring issue with explanation in AI is that explanations tell you why something happened. Past tense. Something has to go wrong for us to fix it. We're not preventing problems, we're offering up excuses as to why they happened. Being able to say that your autonomous car struck a pedestrian because it marked her as a false positive is consolation to no one.

Explanations are not knowledge

An explanation gives us information about a specific decision or prediction. It does not tell us what the machine knows. It does not tell us about the knowledge inside the machine that shaped that decision or prediction. If we're using deep learning on particle accelerator data, the AI has some internal model of how to classify particles by their collision characteristics -- which physicists would probably be pretty interested in -- but to get at that knowledge using explanation, we'd have to piece it together by asking about every possible prediction. In the mean time we do not understand the limits of the machine's knowledge, or when and how the machine can fail.

Explanation makes inappropriate trust worst

People anthropomorphize machines. They attribute human intentions and characteristics to things that display the slightest human qualities. We also tend to trust people. Trusting people is important for learning. If I distrust everything you say, I cannot learn from you. If I trust you implicitly, I can accept everything you say without question, which allows me to learn quickly. Since explanation is a human behavior, it primes people to expect other human behaviors from the machine, and because of this, people will tend to over trust the machine.

In 1996 Gary Kasporov lost to Deep Blue, IBM's chess-playing supercomputer. Deep Blue made a very perplexing move that threw Kasporov through a loop. In an interview with Time Kasporv said:

It was a wonderful and extremely human move [...] I had played a lot of computers but had never experienced anything like this. I could feel -- I could smell -- a new kind of intelligence across the table.

The problem was that the move was a glitch. But because Kasporov believed it was an intentional move made by an opponent on a higher plane of intelligence, he played around it rather than exploiting it. It cost him the match.

Another game-playing machine from IBM nearly got a wrong response by Jeopardy host Alex Trebek. The answer (in Jeopardy, the host gives an answer to which the player responds with a question) Trebek gave was something along the line of "This oddity of Olympian gymnast George Eyser". Ken Jennings responded "What is missing a Hand?", which was incorrect. Watson responded "What is a leg?", which Trebek initially accepted because George Eyser was missing a leg. The issue was that the correct response should have been "What is missing a leg?". Trebek assumed that Watson was aware of the context provided by the other players, and that it was playing off Ken Jenning's response. I'd argue that most of language is implicit in context -- it certainly helps to convey more information with fewer words -- and so it's a very natural assumption to make. But the score had to be corrected after Trebek was notified of the error.

Interestingly, Trebek should have been aware of this because Watson had previously repeated an incorrect response given by a contestant.

In both of these cases, human users were made to inappropriately trust an AI that activated their user's innate psychological biases. To appropriately modulate trust and to ensure that human's interact appropriately with their AI, AI developers should conduct extensive user experiments and design with the psychology of social interaction in mind.

You shouldn't trust black box AI to begin with

The problem with being made to trust a black box model, like deep learning, is that black box models should never be trusted. You should assume that they will go catastrophically wrong out of nowhere, because they do. You can dramatically change the prediction of an image classifier by adding stickers to a stop sign (cite), or changing a single pixel in an image (cite). Even the most robust modern deep learning models are incapable of accurately representing the limits of their knowledge (cite). And being vulnerable to odd or malicious data is argued to be an inherent feature of these models (cite & discussion). Sure, they can be made to give you an approximation of their certainty in their answers, but because their knowledge is stored as an arbitrary mapping from inputs to outputs, that knowledge -- and that uncertainty -- is nonsensical. Don't use black box AI when anything important is at stake.

This issue is compounded by XAI work that seeks to use black box models to learn to generate plain-text explanations for black box predictions. Black boxes explaining black boxes.

Capturing the spirit of XAI

To use AI in high-risk high-impact domains, we need AI that are completely transparent and intuitive to the humans that will be using them; not just data scientist and AI experts, but the decision makers. This is the spirit of XAI. The unfortunate use of the word explanation has encouraged researchers to continue to use dangerous and inappropriate AI models as long as they can develop additional wrapper models to generate plausible explanations for decisions or predictions. But some AI researchers have taken different approaches, focusing instead on interpretable models whose workings can be intuitively understood by human users, or by focusing on embedding machine knowledge directly into human users through teaching (both topics that I will cover in detail in future posts).

Interpretable models are trivially explainable. The difficulty is that making models that are interpretable, general, and powerful is really, really hard. Then there's making them fast...

Teaching is a promising approach. If we can transfer machine knowledge into a human, then we no longer need to ask an AI questions about its behaviour. Those questions become introspection. I can decide how I feel about making a decision based on what the machine has taught me. If I feel icky, I can step back and start figuring out why. The issue with teaching is that it is also very hard. Computationally, it involves recursive, back-and-forth reasoning between teacher and learner, which is hard to make work for complex knowledge.

But of course, all of these are temporary problems. The future is bright for AI -- though "Explainable AI" is in bad need of a name change -- and I think we're on the cusp of a major paradigm shift. AI has been going down the wrong path for a long time -- maybe it's always been going down the wrong path. Users are butting up hard against its limits, and are eager to fix them.

Key points

- Explainable AI is about enabling AI in high-risk sectors by developing AI that are completely transparent and intuitive to decision makers.

- The word "explanation" has lead researchers to develop secondary models to explain predictions and decisions made by uninterpretable primary models.

- There are some problems with explanation:

- Explanations don't prevent problems, they offer excuses as to why they happened.

- Explanation is not knowledge. It does not tell us what the machine has learned.

- Explanations make inappropriate trust worse by increasing trust in brittle, unpredictable, and dangerous models.

- Some researchers are focusing on general interpretable models, which are trivially explainable

- Some researchers are focusing on teaching, which embeds machine knowledge into a human mind, which turn questions we'd ask a machine into questions we'd ask ourselves